Howl’s Moving Castle, Gig Economy and Future of Taxes

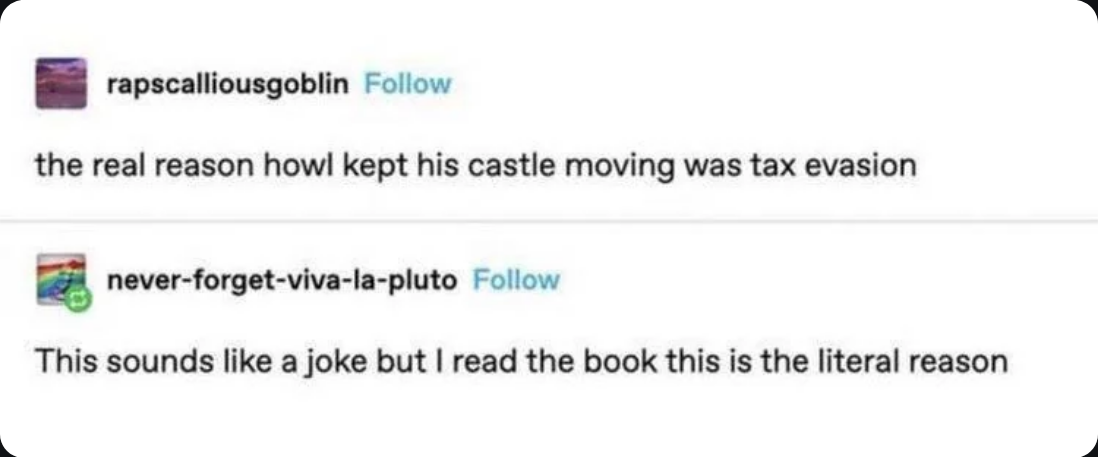

No, Howl’s Moving Castle is not about tax evasion. The elusive, ever-moving wizard Howl refuses to be tied down to one place, creating a home that can shift locations at will. His castle, constantly disappearing and reappearing across different landscapes, isn’t much different from the reality that many remote workers, freelancers, and entrepreneurs live today. In a way, Howl is the first digital nomad.

We’ve been throwing around terms like “digital nomad,” “gig economy,” and “location independence” as if they are old concepts, but in reality, they are incredibly young. The term digital nomad itself originates from a 1997 book by Tsugio Makimoto and David Manners, predicting a workforce of independent work professionals not tied to one place. Fast forward to today: digital nomad visas have only existed for about five years, the gig economy in its current form has been around for two or three, and yet this market is already worth $556.7 billion in 2024. By 2032, it is projected to reach an astonishing $1.8 trillion.

Meanwhile, the concept of tax havens (and evasion), often lumped into the same discussion, is far older. Switzerland and Liechtenstein pioneered the practice in the mid-20th century, creating a framework that many jurisdictions followed. Al Capone famously served jail time for tax evasion in 1931. Yet, while these systems have evolved for decades, digital nomadism and the gig economy are still in their infancy—forcing governments to play catch-up.

Gig Economy:

Work, but Figure Out Your Taxes

If you’ve ever used an app to book a ride, order food, or rent a vacation home, you’ve participated in the gig economy. The UK government defines it as "the exchange of labor for money via digital platforms that actively facilitate matching between providers and customers, on a short-term and payment-by-task basis.”

For workers, it offers freedom and flexibility. But it also brings instability. Gig workers often trade job security for autonomy, sacrificing benefits like health insurance, pensions, and minimum wage protections. And then there’s the tax question.

Most gig workers, especially those juggling multiple income streams across different platforms, operate in a legal gray area. Where do they pay taxes? Their home country? The country where they perform most of their work? The country where the company paying them is based? These questions don’t have easy answers, and for many, figuring out tax residency becomes a logistical nightmare.

Governments are only just beginning to regulate this space. Landmark rulings: like the 2021 UK Supreme Court decision that forced ride-hailing platforms to grant worker protections, signal that tax and labor laws are evolving. But it’s clear that the traditional employer-employee framework is struggling to keep up.

Digital Nomadism:

Work, and Please Pay Taxes Somewhere

A digital nomad is someone who takes their work on the road, logging in from cafés in Bali, coworking spaces in Lisbon, or ski chalets in Switzerland. The idea sounds romantic, and to some extent, it is. But it also raises a fundamental question: where should digital nomads pay taxes?

Most tax systems operate on the assumption that people live and work in the same country. Digital nomads break this model. They may have clients in one country, a business registered in another, and no fixed residence at all. This has led to growing concerns about "nowhere taxpayers", people who live globally but fail to contribute to any national tax system.

Governments are responding. Over 50 countries now offer digital nomad visas, which, in theory, provide a legal and tax-compliant framework for remote workers. But in practice, these visas vary wildly in their tax requirements. Some explicitly exempt nomads from local taxation, while others require them to contribute.

For digital nomads, the challenge is balancing legal compliance with financial efficiency. Some try to maintain tax residency in their home country, filing returns as if nothing has changed. Others attempt to leverage tax treaties to avoid double taxation. And some (intentionally or not) fall into a legal limbo, paying little to no tax anywhere.

Ultimately, digital nomadism is not about avoiding taxes. It’s about redefining them. As remote work becomes the norm, tax laws will have to evolve to accommodate global workers who contribute to multiple economies without being anchored to a single one.

Tax Havens:

Work, and Pay Less

Tax havens are not new. In fact, they’ve shaped global finance for over a century. The earliest versions emerged in the late 19th century when U.S. states like New Jersey and Delaware made it easy for corporations to incorporate with little regulation. By the 1920s, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and a handful of Caribbean territories were crafting laws to attract international wealth.

By the 1980s, the rise of financial globalization turbocharged the role of tax havens. According to How We Got Here: A Historical Perspective on Tax Fraud and Tax Evasion, about half of all multinational investments are routed through tax havens, and up to a trillion dollars in tax revenue is lost annually due to avoidance strategies.

Despite ongoing crackdowns from the OECD and EU, tax havens persist because they serve a crucial function: providing competitive tax environments for mobile capital. And as work becomes more mobile, individuals, not just corporations, are looking for similar flexibility.

The debate over tax havens often revolves around ethics. Are they legitimate financial tools, or are they mechanisms for the wealthy to avoid paying their fair share? The truth is more complicated. Many small jurisdictions rely on financial services as a cornerstone of their economies. While some clearly facilitate money laundering and tax evasion, others operate as well-regulated financial hubs offering legal tax minimization strategies.

For individuals, especially digital nomads and entrepreneurs, tax havens present an interesting proposition. Setting up a company in a low-tax jurisdiction can significantly reduce tax burdens, but it also comes with legal complexities. Banking restrictions, blacklists, and compliance requirements mean that tax havens are not the easy escape they once were.

We Don’t Need to Be Tied Down, But We Do Need Regulation

For decades, the idea of work was tied to geography. You lived where you worked, and you paid taxes accordingly. But in the past few years, we’ve seen this structure unravel. Work is no longer bound to a single country, a fixed office, or even a traditional employment model. More people are ditching long-term contracts in favor of freelancing, consulting, or short-term projects.

This shift is not temporary. It’s not a “trend” or a “loophole” that governments will eventually crack down on. It’s a fundamental transformation in how people work and live. And with more people choosing multiple residencies and remote work, policies will have to change to accommodate them.

Right now, the reaction to this shift is mixed. Some governments welcome remote workers, offering digital nomad visas and residency by investment programs. Others are more skeptical, seeing them as tax dodgers or economic free riders. But here’s the reality: the vast majority of global citizens are not trying to evade taxes, they just don’t fit into the old system.

What Needs to Happen Next

Instead of vilifying the flexibility of global living, we need new systems in place that reflect how the world is developing. This means:

- More residency-by-investment programs that recognize the legitimacy of global entrepreneurs and mobile professionals.

- Better digital nomad visa structures that provide clear tax obligations, legal protections, and long-term options for those who want them.

- Legitimization of the gig economy through policies that account for its scale and economic impact.

The world is becoming more borderless in how it works; laws will need to evolve accordingly. The era of fixed-location employment is fading, and while the final form of this shift is still unclear, one thing is certain: the old system isn’t coming back.

The future of work isn’t about escaping obligations—it’s about redefining them. And maybe, just maybe, we should stop thinking of global citizens as tax evaders and start seeing them as pioneers.

Member discussion